Here is a long overdue write-up on ham radio… I have quite a few friends that need help getting started and without a direction or some background knowledge, its daunting. Keep in mind, this isn’t comprehensive, but it’s a good start. I may expand this write-up in the future….any changes or additions I make will be published in future articles.

The first thing you need to consider to become a Ham radio operator is licensing. There are three categories of license so let me explain each. The technician’s class is the easiest to get, the exam only covers basic radio theory, FCC regulations, and safety; it is an introductory license to many but for people that want to only use their equipment for local commo (it allows for VHF and UHF transmission only), it’s the only license they need. The next step up is the general class license; it allows for commo on all amateur radio bands (exclusions apply) which will give you worldwide capabilities. As you would expect, the exam is more difficult; it covers more advanced radio theory, antenna designs, radio wave propagation, but thankfully they have deleted the Morse code portion of the test and it is no longer a requirement. With a few weeks practice however, you can pass the exam no problem. The final license is the extra class; this license is for serious Ham radio enthusiasts and as you would expect, the test is much more difficult. Extra class operators often compete in ham contests and collect QSO cards from around the world. I would compare the three levels of license to a high school diploma (technicians class), a college degree (general class), and a PHD (extra class). If you’re looking to use your ham equipment casually but want the capabilities to talk to someone across the country (especially in a crisis situation), the general class is the way to go. I hold a general class license and I can transmit on all bands, but specific frequencies within those bands have been set aside for extra class license holders only.

Several books you may want to consider buying in preparation for your test are study books written by Gordon West. He writes books for each category of license and each text includes actual test bank questions. These books however, don’t do an excellent job of explaining radio theory, different antenna designs, or other topics you may want to know as a ham… they cover test prep material almost exclusively. If you’re looking to enhance your knowledge, you’ll want to expand your library… and believe it or not, there is a book Ham radio for dummies. The test questions and practice tests are available online as well. If you go on the ARRL website, you’ll find practice exams, local test dates, and local ham clubs… and hams are a very friendly bunch overall, you will have no trouble finding people help you get started.

expand your library… and believe it or not, there is a book Ham radio for dummies. The test questions and practice tests are available online as well. If you go on the ARRL website, you’ll find practice exams, local test dates, and local ham clubs… and hams are a very friendly bunch overall, you will have no trouble finding people help you get started.

Now that you know what the licensing requirements are, let me explain the different bands so you know which license you should strive for. There are two basic categories, HF or high frequency, and VHF/UHF or very high frequency/ultra high frequency. The HF bands have the ability to “skip” off of different layers of the atmosphere and transmit over very long distances. The VHF bands are primarily line of sight transmission but have the ability to use repeaters to extend the range of your signal. The following is a list of the most commonly used bands and a brief explanation of each:

High frequency bands: General and Extra class have privileges

160 meter – Frequency limits: 1.8–2.0 MHz. This is a night owl band, meaning the radio wave propagation is best at night. If you think about the AM radio in your car, the best reception is at night… and those frequencies are around 1.0 MHz.

75/80 meter – Frequency limits: 3.5–4.0 MHz. This band is best evenings and nights. The patriot net is run at 8pm central time on this band because it can be heard from across the county quite easily.

40 meter – Frequency limits: 7.0–7.3 MHz. This band is best best days and evenings although I’ve had good success with it at night as well.

20 meter – Frequency limits: 14.0–14.350 MHz. This band is best days and nights. My longest contact to date was a station in London, England from my home on the east coast of the US. I regularly make contact with stations in the Midwest, Florida, Texas, etc. on this band.

15 meter – Frequency limits: 21.0–21.450. This band is best days. You may notice that the shorter the radio wave, the better it is for use during daytime operation. Longer waves are unable to skip because of atmospheric interference caused by the sun… whereas at night, the interference is gone; shorter waves as a rule pass right through.

11meter – Frequency limits on this band are not even a consideration. The 11 meter band is designated as for Citizen Band (CB) radio transmission. You need separate equipment to transmit on these frequencies and the equipment has channels assigned to specific frequencies.

10 meter – Frequency limits: 28.0–29.700 MHz. This band is best days but in my experience, really noisy at night.

VHF/UHF bands: Technician, General, and Extra class have privileges

6 meter – Frequency limits: 50.0–54.0 MHz.

2 meter – Frequency limits: 144.0–148.0 MHz

70 cm (often called the 440 band)– Frequency limits: 420.0–450.0

The VHF/UHF bands are good any time of the day since they are line of sight transmission (they normally don’t allow for atmospheric skip but anomalies can happen where windows open up for longer range transmission). The range can be extended on each band by using repeaters. To explain what a repeater is, imagine another radio that accepts your  signal (encrypted with a frequency offset and PL tone that you program into your radio) and then broadcasts it again on the selected frequency so it can be heard over a larger area. I suggest purchasing a repeater directory from ARRL so you know which frequencies and PL tones to use for the repeaters in your AO. Keep in mind the list of frequencies above is not comprehensive. Other bands do exist but these bands listed are most commonly used (atleast by me anyway). The bands I’ve excluded from this list fill in the frequency gaps quite a bit but there are still some frequencies off limits to amateur radio; for example, emergency communications are around 150MHz, FM radio is around 100MHz, and there are others used by railroad, GMRS radio, etc. that hams cannot transmit on.

signal (encrypted with a frequency offset and PL tone that you program into your radio) and then broadcasts it again on the selected frequency so it can be heard over a larger area. I suggest purchasing a repeater directory from ARRL so you know which frequencies and PL tones to use for the repeaters in your AO. Keep in mind the list of frequencies above is not comprehensive. Other bands do exist but these bands listed are most commonly used (atleast by me anyway). The bands I’ve excluded from this list fill in the frequency gaps quite a bit but there are still some frequencies off limits to amateur radio; for example, emergency communications are around 150MHz, FM radio is around 100MHz, and there are others used by railroad, GMRS radio, etc. that hams cannot transmit on.

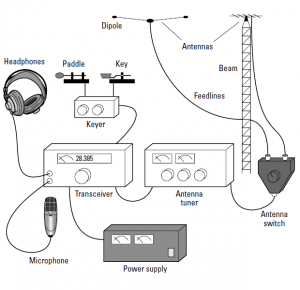

The next consideration is equipment. I have a write up on a budget handie talkie that can be found here. For anyone looking for more than local commo, lets take a look at longer range equipment. If you have a limited budget (and lets  be honest, who doesn’t) I would suggest getting a radio that is an “all band” transceiver. The advantage here is you buy one radio and you can transmit on all bands… the drawback is, if that radio goes down, your unable to transmit on any bands. An all band model I would suggest is the Yaesu FT857D. I have a Yaesu FT100D and love it… but it is not without it’s faults; it has a small face (as does the FT857D) with limited buttons, this means there are lots of hidden menus and you need to have the manual handy until you get used to its operation… and it has a maximum of 100 watt output but I rarely have a problem talking to hams several thousand miles away. The FT100D is no longer made but I believe the FT857D is the replacement in the Yaesu line. It should cost you under $1000 for the unit… when you think about the cost of an HF unit plus a VHF/UHF unit together; $1000 doesn’t seem too bad. If you want to spend more money, you can get much bigger units that are more user friendly and capable of putting out more watts… but in my experience, it’s really not necessary. There are other units out there you may find more appealing or may come recommended from another ham, but regardless of what you buy, stick with a decent name brand like Icom, Kenwood, or Yaesu.

be honest, who doesn’t) I would suggest getting a radio that is an “all band” transceiver. The advantage here is you buy one radio and you can transmit on all bands… the drawback is, if that radio goes down, your unable to transmit on any bands. An all band model I would suggest is the Yaesu FT857D. I have a Yaesu FT100D and love it… but it is not without it’s faults; it has a small face (as does the FT857D) with limited buttons, this means there are lots of hidden menus and you need to have the manual handy until you get used to its operation… and it has a maximum of 100 watt output but I rarely have a problem talking to hams several thousand miles away. The FT100D is no longer made but I believe the FT857D is the replacement in the Yaesu line. It should cost you under $1000 for the unit… when you think about the cost of an HF unit plus a VHF/UHF unit together; $1000 doesn’t seem too bad. If you want to spend more money, you can get much bigger units that are more user friendly and capable of putting out more watts… but in my experience, it’s really not necessary. There are other units out there you may find more appealing or may come recommended from another ham, but regardless of what you buy, stick with a decent name brand like Icom, Kenwood, or Yaesu.

In addition to the basic transceiver, you will also need antennas. Again, I would suggest getting a multiband antenna. I would suggest something along the lines of a Challenger DX… it is lightweight (just over 20 pds), has decent height (just over 30 ft), and is capable of transmitting on bands from 2m up to 80m. You can also look into buying a multiband for HF (like a Butternut HF6V) and a multiband for VHF (like a Hustler G6-270R). You will then have a  dedicated antenna for each. The multiband approach saves you the trouble of having an “antenna farm” set up on your property and less initial outlay in equipment. The drawbacks to this approach are decreased transmission range and the possibility of needing an antenna tuner. The antennas I listed above are omnidirectional meaning they transmit in all directions instead of focusing your signal in one specific direction… when a directional antenna is used, the signal is transmitted and received from one direction primarily and the power is focused in that direction…. they are much more expensive, but also much more efficient/effective. The other drawback is an antenna tuner may be needed since these are multiband antennas; a tuner tricks your radio into accepting the signal and giving a decent SWR reading. SWR is short for standing wave ratio. Essentially it is a measurement of the radios ability to transmit with a given antenna. The closer the SWR is to 1:1, the better the signal will be. With a multiband antenna, the radio may not be reading a decent SWR because of multiple wire lengths on the antenna distorting the signal, so it needs to be tricked into accepting the signal you want for a specific frequency… which requires a tuner. Decent tuners can be purchased for several hundred dollars… still cheaper than purchasing an antenna for each band you want to transmit on.

dedicated antenna for each. The multiband approach saves you the trouble of having an “antenna farm” set up on your property and less initial outlay in equipment. The drawbacks to this approach are decreased transmission range and the possibility of needing an antenna tuner. The antennas I listed above are omnidirectional meaning they transmit in all directions instead of focusing your signal in one specific direction… when a directional antenna is used, the signal is transmitted and received from one direction primarily and the power is focused in that direction…. they are much more expensive, but also much more efficient/effective. The other drawback is an antenna tuner may be needed since these are multiband antennas; a tuner tricks your radio into accepting the signal and giving a decent SWR reading. SWR is short for standing wave ratio. Essentially it is a measurement of the radios ability to transmit with a given antenna. The closer the SWR is to 1:1, the better the signal will be. With a multiband antenna, the radio may not be reading a decent SWR because of multiple wire lengths on the antenna distorting the signal, so it needs to be tricked into accepting the signal you want for a specific frequency… which requires a tuner. Decent tuners can be purchased for several hundred dollars… still cheaper than purchasing an antenna for each band you want to transmit on.

I recommend this equipment because I’ve either dealt with it myself of have read good reviews. All told, this equipment should run you in the $2000 range… and that includes all the odds and ends you’ll find yourself picking up from time to time like antenna duplexers, coaxial cable, PL259 connectors, etc. You can purchase all of the items I’ve mentioned from places like

Ham radio outlet www.hamradio.com

Texas towers www.texastowers.com

Amateur electronic supply www.aesham.com

Well, that is Ham radio in a nutshell… there is much much more info that could be included in this writeup but this is really just a primer. I’m sure I haven’t answered all or your questions but this is a start. One thing I purposely left off is installation… that is a whole different ball game… it’s simple but grounding considerations need to be adhered to (for power and lightning) or you’ll be spending money on new equipment really quick. As I mentioned earlier, best to start a library on ham radio resources and techniques and learn as you go.

Good article. Nice and concise.

A few other recent articles on some other sites are:

http://www.itstactical.com/digicom/comms/the-ultimate-guide-to-learning-about-radio-communication-and-why-you-should/

http://www.itstactical.com/digicom/comms/ultimate-radio-communication-guide-what-to-look-for-in-a-handheld-transceiver/